The Singer’s Library: Don’t Sweat the Technique

A stylistic and pedagogical guide to hip-hop and rap fills a glaring gap in the performance literature.

In 2017, hip-hop surpassed rock music to become the most popular genre in the United States, according to Nielsen Music’s year-end report.1 In 2023, Spotify announced that nearly a quarter of all streams on the platform were of hip-hop music, making it one of the most listened-to genres across the globe.2 It was further highlighted in 2025 at the halftime show of Super Bowl LIX, which featured Grammy Award® and Pulitzer Prize® winning rapper Kendrick Lamar.

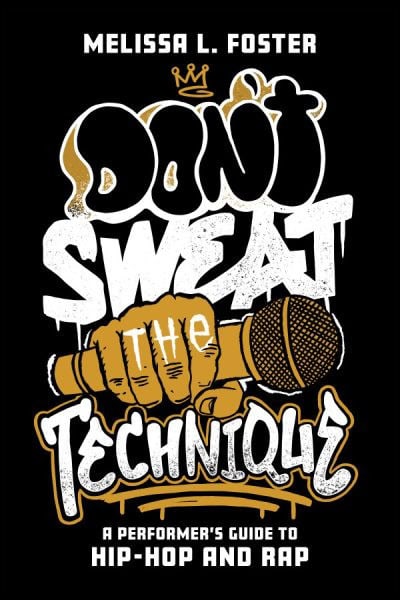

Despite its popularity, however, there have been relatively few vocal pedagogy books related to the history and performance practice of the genre. This gap has recently been filled by professor and author Melissa L. Foster with the release of Don’t Sweat the Technique: A Performer’s Guide to Hip-Hop and Rap (Rowman & Littlefield, 2023). My conversation with the author, excerpted below, offers a preview of the themes addressed in the book.

In the introduction to the book, you state, “Don’t Sweat the Technique: A Performer’s Guide to Hip-Hop and Rap is about both the history and the pedagogy of hip-hop, and one needs the other…, This book is structured on the pillars of both history and technique, because they are intertwined.” Can you explain what you mean by this? Why is it important to feature both?

This idea is not mine alone as far as popular music being influenced by pop culture. There are really wonderful books that talk about socio-political culture influencing the pop sound, and the music then influencing movements [in the culture]. That’s not unique to hip-hop, but I do think it’s especially true.

It’s been said that hip-hop is Black people’s CNN, because it’s sort of a platform to bring attention to and shine a spotlight on issues that are happening in the Black community, like police brutality or redlining. I could go on and on. With hip-hop, the development and the evolution of the different styles and genres is directly impacted by what’s happening to the people and the artists and what’s going on around them. The sound of the genre itself is evolving based on what’s changing in the culture. One influences the other: history influences the music, music influences the history.

Early in the book, you write, “I think that rap is for anyone and everyone that loves to rap.” This sentiment is echoed later in your interview with Noah, who says, “There shouldn’t be this elitist glass ceiling above anybody that just wants to rap about their story on a nice beat—that should be accessible to everybody. I always say everybody can rap.” What do you think are some of the primary obstacles preventing people from exploring, enjoying, and engaging in this genre?

This is just my opinion, but what I’ve experienced with my students—with rap music in general, or if they’re called into an audition for a musical that has rap—it’s a scary genre because of the fear of being inauthentic in your presentation. So much of it is rooted in African American culture, and so many rap artists are African American, so I think people might feel that they don’t have the permission to rap. I don’t think that’s true at all. I think it’s really for everyone. I just think that everybody has an authentic story to tell or an authentic viewpoint from which and through which to approach this style. And so, as long as that happens, I think everybody should be rapping all day long.

You indicate that the book is for anyone who is interested in learning how to rap—even beginners—whether they are 16 or 61. Therefore, you set out to develop an organized approach for studying the craft of rapping. How would you explain to beginners the benefit of an organized approach as opposed to simply jumping in?

You know, jump in and try things. But then if you hit a stumbling block, you might not know why. That’s an argument for [an organized approach] in and of itself, because you won’t really know why you’re tired or why you keep getting off the beat or not getting through phrases. You might say, “Okay, well, I need to take bigger breaths.” But is that necessarily the case?

I’m sure people would say this about classical music, and I certainly think about it when I’m teaching musical theatre: it’s not linear, because every student is different with what they need and where they’re coming from. It’s scaffolding. If you jump right to floor four and you didn’t build the basement, you’re going to have a problem. That’s why I start in a way that I think is accessible. Working in a scaffolded way helps avoid pitfalls and frustrations that you have to solve.

Review:

Don’t Sweat the Technique: A Performer’s Guide to Hip-Hop and Rap is divided into two primary sections. Part I: History and Influence provides a detailed timeline of hip-hop’s development from the 1960s to the present, noting seminal figures, events, and works. To accompany this section, a companion website provides a YouTube playlist (230 videos) and a Spotify playlist (16 hours and 45 minutes long) of all the songs mentioned in the book. These extensive lists of artists and songs are representative of the many eras, styles, and subgenres Foster refers to in the text. She frequently references the playlists, encouraging readers to inform their ears by interrupting her own writing with appeals of “Go listen to …”

Part II: Vocal Technique dives into the “how” of hip-hop and rap performance. It touches on requisite pedagogical elements, like posture, breath, resonance, and articulation. It also covers elements of performance practice, like microphone techniques, storytelling, and “rhythm and flow.”

The final chapter, though housed within Part II, is essentially a third part of the book, which includes interviews with MCs on “how they approach the art of rapping.” The conversations with 14 artists are wideranging and touch upon many of the topics from earlier chapters. This includes discussing breathing techniques with Anonymuz, a conversation on finding authenticity with redveil, exploring Ausar’s thoughts on the differences between live performance and recording sessions, and AC Tatum’s predictions for the future of rap music.

Foster acknowledges that many topics she covers have entire books dedicated to the same subjects. As such, her book serves as a survey—a nonexhaustive guide. However, she includes references and a bibliography for further, more in-depth study. She also chose to write the book in what she calls “simple and direct language” so as to make the material accessible and digestible.

Foster does not attempt to provide quick or easy answers to issues that require nuance and context. In chapter 7, for instance, she assumes the perspective of a reader and asks, “Hey, Black Professor Lady, please tell me in clear and uncertain terms who gets to enjoy, create, perform, analyze, and profit from hip-hop. Most importantly, do I get to enjoy, create, perform, analyze, and profit from hip-hop?” The honest answer she offers is “I don’t know. I’m not here to tell you who gets to own hip-hop. It’s complicated, the jury is out, and if anyone tells you they are the arbiter of who gets to deal in hip-hop (or, more frighteningly, who doesn’t), I suggest you call BS.”

Foster articulates the need for the book in the introduction: “There are so many books on singing…but if you are trying to learn to rap, well, it’s harder to find a book that talks about that.” Taking on such a venture, then, requires extensive experience with the genre and a deep knowledge of vocal technique. But it also requires courage to do what has not been done. Foster clearly demonstrates in her writing that she is up to the task.

Early hip-hop artists who were pioneering a new form of musical expression provided foundations upon which generations of artists have made their own contributions. In the same way, Don’t Sweat the Technique: A Performer’s Guide to Hip-Hop and Rap stands to inspire both performers and pedagogues to delve into a style of singing that, while immensely popular, has been underexplored in the vocal literature thus far.

Footnotes:

- Alexander Frandsen, “A Data History of Popular Hip-Hop,” Storybench; www.storybench.org/a-data-history-of-popular-hip-hop/#:~:text=According%20to%20Nielsen%20Music’s%202017,Rap%20Songs%E2%80%9D%20list%20since%201989 (accessed March 1, 2025).

- For the Record, “Nearly a Quarter of All Streams on Spotify Are Hip-Hop. Spotify’s Global Editors Reflect on the Genre’s Growth,” Spotify, August 10, 2023; newsroom.spotify.com/2023-08-10/hip-hop-50-murals-new-york-atlanta-miami-los-angeles/ (accessed March 1, 2025).