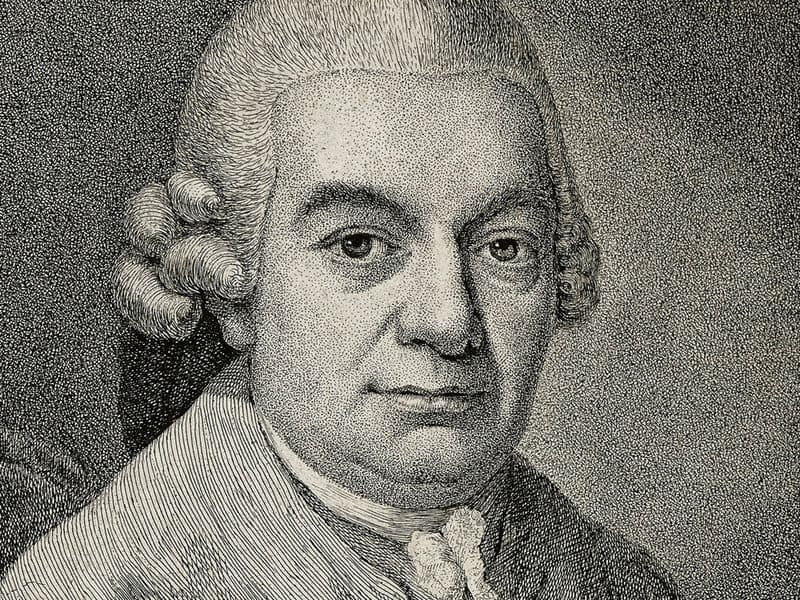

I first encountered the songs of Carl Phillip Emmanuel Bach when I was putting together a concert of 18th century music with some friends. While I’ve been singing the cantatas of Johann Sebastian Bach for decades, these miniatures were very different, yet unexpectedly delightful. The songs are filled with surprising twists of harmony, rapid changes of dynamics and textures, and sculpted melodies that explore wide ranges, exemplifying the Empfindsamer Stil (sensitive or emotional style).

I was hooked: the melodies were so singable and elegant! And the highly dramatic style appealed to my love of expressive text settings. So began my exploration of one of the most obscure repertoires in song literature: the music written in the last third of the 18th century. Of course, at the time this music was difficult to find, much less to include on programs. Editions of CPE Bach songs were sparse and didn’t contain more than a handful of songs drawn from several collections. That’s why the new complete edition of Bach’s works, nearing completion by the Packard Humanities Institute, is so significant. For the first time since their publication, Bach’s songs are becoming widely available for musicians to peruse, study, and perform. The editions are beautiful, scholarly, and incredibly affordable. Individual songs are even available for free download.

I’d like to take you through several of my favorite Bach songs, so you can have a taste of his inventiveness and brilliance in the genre. First up: a song from his first published collection, Gellerts Geistliche Lieder und Oden [Gellert’s Spiritual Songs And Odes]. Christian Furchtegott Gellert was celebrated throughout Germany as a brilliant poet and thinker. He was known both for charming fables and for spiritual and devotional poetry. These poems are meditations on human existence and morality, generally with a spiritual cast. Strophic and sometimes running over ten verses, they were intended to be read and studied in the home.

These confessional, self-examining poems bring out Bach’s most adventurous harmonic explorations; Das natürliche Verderben des Menschen [the Natural Corruption of Humanity] (Wq 194/33) is a fine example of this. The voice begins its self-interrogation in a low, insinuating register. Sharp contrasts in dynamics, range, and rhythm dominate this piece, which defeats expectation virtually in every bar. This tiny 17-bar song is so eventful that it feels much longer; but the poem itself runs a full twenty verses, all of which explore in ever greater depth humanity’s weaknesses, sometimes in compellingly contemporary language.

Bach’s later song collections also focus on spiritual themes: he set versified Psalm settings by Johann Andreas Cramer and two volumes of devotional poetry by a minister and colleague, Christoph Christian Sturm. While these latter sets are less ambitious, vocally and melodically, than the Gellert songs, they are no less daring harmonically. A terrific example of the Sturm lieder is Der Tag des Weltgerichts [the World’s Judgment Day] (Wq 197/13). The song opens with a brief keyboard flourish, initiating the relentless dotted figures, evoking thunder, which underlies the first half of the text. The voice part is supported by a very full harmonic underpinning in the right hand, and emphasizes the halting, short-breathed phrases that describe the terror of the end of the world. The final line of each verse is given to a plea for mercy to God, and at this point the music evaporates into a long, arching chorale-like line, beneath which the keyboard plays staccato offbeat chords; this texture reinforces the fear and shock of the subject in an almost orchestral manner.

If you feel that programming long strophic meditations on human weakness or the end of the world is unappealing, let me hasten to tell you about Bach’s delightful secular songs. These were published in various collections, and feature poetry by some of the most revered writers of the late 18th century. Ranging from whimsical all the way to deeply sardonic, this collection contains both miniatures and elaborate through-composed works.

Advertisement

One example is the charming Die Küsse [The Kisses] (Wq 199/4), which narrates a lover’s dilemma; an older, ‘wiser’ man has counseled him that too much kissing is an excess to be avoided, so he attempts to restrict himself with his beloved. This song is written in a binary form: the first section, where the young man takes the criticism of his behavior to heart, cadences in the relative minor; the second section begins with the opening melody, as he attempts to fulfill his plan with his sweetheart present, but the melody, like his scheme, goes awry as she gently mocks him and reminds him that the only critic that matters is she herself!

And I must mention my favorite piece in this collection: the brilliant cantata for voice and piano, Die Grazien [The Graces] (Wq 200/22). The poem, by one of the Enlightenment’s most brilliant poets, Heinrich Wilhelm von Gerstenberg, flows seamlessly between poetry and prose. It is a masterpiece of misdirection and wit. The plot turns on a case of mistaken identity involving the mythical Three Graces and the narrator’s sweetheart, and the language veers between flowery imagery and deadpan sarcasm. The inventiveness of this lengthy text is more than equaled by Bach’s music. Clearly conceived for keyboard (as opposed to an instrumental ensemble), the cantata flows from recitative to arioso to metrical aria and back again, responding to every shift in tone with imaginative and original gestures.

Crucial to performing any of these works is sympathy with the texts. Again, the new editions of these songs are indispensable to non-German-speaking singers, as they provide complete translations for every song, every verse, on the PHI website and in offprint editions. As the translator of all these poems, I can attest that there are many great works here; they will amply reward study and consideration.

So, can these pieces, charming, moving, and profound, find a home in the modern recital program? I am certain that they can. The longer and more complex secular works are neglected gems, and definitely deserve more exposure on concert programs. They would be completely convincing on a modern piano, and the keyboard writing is imaginative and independent enough to provide satisfying challenges to an accompanist. A set of spiritual songs could start a recital or be offered during a worship service; or a song by Bach could be programmed alongside some of Beethoven’s settings of Gellert poetry. Don’t be put off by the long string of stanzas that many of these songs have! Most will work beautifully with a well-chosen subset of verses, and like all strophic songs, afford an opportunity to create variety through shifts of dynamic, tone color, and text articulation. Now that the full body of Bach’s songs is available to performers, it’s high time that they join the song literature and earn their place as great exemplars of the Lied.

Downloads of PDFs and translations available at https://www.cpebach.org/